The internet doesn’t forget. Ask anyone who’s been punished by the brutal truth of the web. The internet doesn’t care that you didn’t really mean what you said in that tweet. The internet doesn’t care that you were super drunk in college and that was a one time thing. The internet doesn’t care that you’re a different person now, and the past is the past.

If you’ve done it, there’s some record of it online. The internet never forgets.

But that doesn’t mean that search engines, the tour guides of the internet, have the same ironclad memory. And thanks to a recent court ruling, search engines are set to be forced into forgetting. It’s a digital lobotomy – and it’s just beginning.

Should Google be forced to remove search results upon request? Let us know in the comments.

In May, The Court of Justice of the European Union handed down a controversial ruling regarding search results and requests to remove them.

“An internet search engine operator is responsible for the processing that it carries out of personal data which appear on web pages published by third parties…Thus, if, following a search made on the basis of a person’s name, the list of results displays a link to a web page which contains information on the person in question, that data subject may approach the operator directly and, where the operator does not grant his request, bring the matter before the competent authorities in order to obtain, under certain conditions, the removal of that link from the list of results,” said the Court.

And thus, the so-called “right to be forgotten” was born. Basically, the ruling makes Google and other search engines responsible for removing results at the request of individuals – in some cases. The decision to remove search results will be up to the search engines, but if agreements cannot be made between search engine and petitioners, then off to court they’ll go.

More from the ruling:

So far as concerns, next, the extent of the responsibility of the operator of the search engine, the Court holds that the operator is, in certain circumstances, obliged to remove links to web pages that are published by third parties and contain information relating to a person from the list of results displayed following a search made on the basis of that person’s name. The Court makes it clear that such an obligation may also exist in a case where that name or information is not erased beforehand or simultaneously from those web pages, and even, as the case may be, when its publication in itself on those pages is lawful.

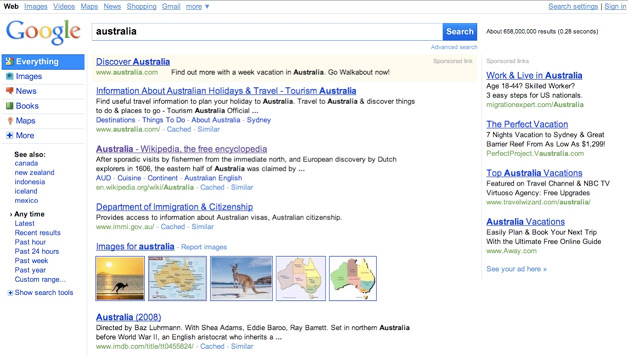

The Court points out in this context that processing of personal data carried out by such an operator enables any internet user, when he makes a search on the basis of an individual’s name, to obtain, through the list of results, a structured overview of the information relating to that individual on the internet. The Court observes, furthermore, that this information potentially concerns a vast number of aspects of his private life and that, without the search engine, the information could not have been interconnected or could have been only with great difficulty. Internet users may thereby establish a more or less detailed profile of the person searched against. Furthermore, the effect of the interference with the person’s rights is heightened on account of the important role played by the internet and search engines in modern society, which render the information contained in such lists of results ubiquitous. In the light of its potential seriousness, such interference cannot, according to the Court, be justified by merely the economic interest which the operator of the engine has in the data processing.

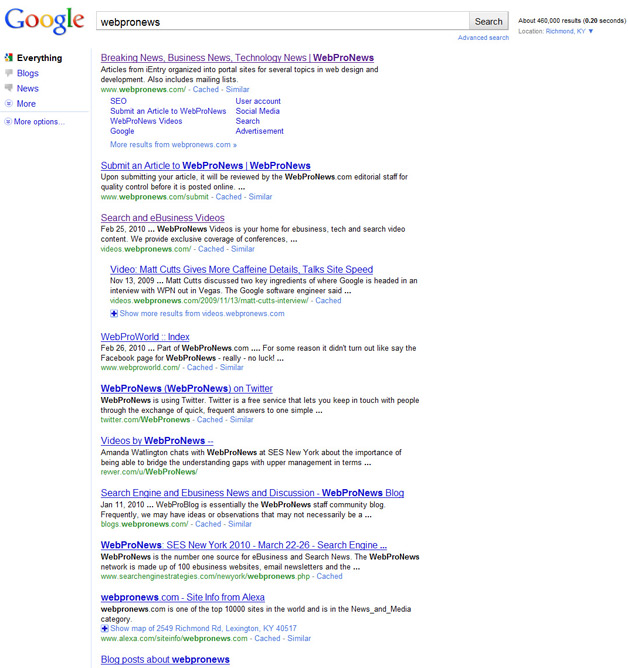

It’s an interesting take on what a search results page really is – an “interconnector” of information. In a way, the court said that Google kind of creates its own content, its own narrative about any given person through a search results page for said person. But more on this later.

This “right to be forgotten” has been the cry of many for years. Naturally, people don’t want every little thing they’ve ever done and every little thing they’ve ever been associated with appearing in a basic Google search for their name. This particular ruling from the EU court stems from the case of Mario Costeja, of Spain, who complained of an auction notice of his repossessed home, which is now resolved, continuing to show up in Google search results, infringing upon his privacy.

As you would imagine, Google’s argument is that being forced to remove certain search results simply because an individual doesn’t like them amounts to censorship.

“[The ruling is] disappointing…for search engines and online publishers in general,” said Google of the ruling.

But they complied, and soon the requests began to flow – 12,000 of them even before Google launched a reporting tool for concerned parties to air their search result grievances. After that, the numbers skyrocketed.

“In evaluating your request, we will look at whether the results include outdated information about your private life. We’ll also look at whether there’s a public interest in the information remaining in our search results—for example, if it relates to financial scams, professional malpractice, criminal convictions or your public conduct as a government official (elected or unelected). These are difficult judgements and as a private organization, we may not be in a good position to decide on your case. If you disagree with our decision you can contact your local DPA,” explains Google.

Apparently, Google agreed with the petitioners on some requests, and now, Google is starting to forget.

“This week we’re starting to take action on the removals requests that we’ve received,” a Google spokesman said. “This is a new process for us. Each request has to be assessed individually, and we’re working as quickly as possible to get through the queue.”

Google has begun to remove search results and add disclaimers at the bottom of results pages – basically saying that some search results may have been removed in order to comply with EU law.

Google had this to say:

We look forward to working closely with data protection authorities and others over the coming months as we refine our approach. The CJEU’s ruling constitutes a significant change for search engines. While we are concerned about its impact, we also believe it’s important to respect the Court’s judgment and are working hard to devise a process that complies with the law.

When you search for a name, you may see a notice that says that results may have been modified in accordance with data protection law in Europe. We’re showing this notice in Europe when a user searches for most names, not just pages that have been affected by a removal.

Clever. I may be a little heavy-handed in my reading of this, but to me it sounds like Google’s subtle way to express their disappointment in the EU’s ruling. Instead of simply adding that disclaimer to pages where they’v actually yanked results, Google wants users to know on every page that the man is holding them down…man. You have incomplete search results, and you know who’s fault it is.

Whether that’s the case or not is moot. The salient aspect of this whole issue is that it’s part of bigger trend – one that might be out of Google’s control. They can continue to cry censorship and express “disappointment” in rulings that hamper their ability to provide complete search results – but the world seems to be turning against them in this regard.

In late 2012, an Australian high court likened Google to a publisher, saying,

“Google Inc is like the newsagent that sells a newspaper containing a defamatory article. While there might be no specific intention to publish defamatory material, there is a relevant intention by the newsagent to publish the newspaper for the purposes of the law of defamation.”

Instead of simply being a ‘link-lister’, Google was deemed a publisher of the publishers, of sorts. The distinction was made even muddier when the court, ruling on a lawsuit in which a man sued Google for associating his name and image with (untrue) claims of ties to organized crime, talked about Google Image results being a “cut and paste creation” – as in content created by Google.

Here, Google was seen as publisher and therefore liable for defamation.

“It follows that, in my view, it was open to the jury to conclude that Google Inc was a publisher – even if it did not have notice of the content of the material about which complaint was made. Google Inc’s submission to the contrary must be rejected. However, Google Inc goes further and asserts that even with notice, it is not capable of being liable as a publisher ‘because no proper inference about Google Inc adopting or accepting responsibility complained of can ever be drawn from Google Inc’s conduct in operating a search engine,’” said the court.

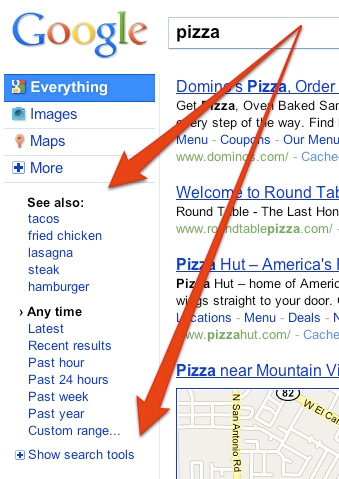

And then there are the various autocomplete woes, wherein Google has been fined for their autocomplete suggestions. We’ve seen this happen all across the world – France, Japan, Italy, and more. The fact that Google’s autocomplete results are not manual, carefully chosen and suggested straight from the brains of Googlers (and are instead based on algorithms and search frequency) hasn’t stopped international courts from finding Google responsible for what it suggests in any given search.

The common thread between all of these cases, including the most recent “right to be forgotten” ruling, is that Google is ultimately responsible for what it provides in a search.

You have to imagine that this is just the beginning, and Google’s fairly weak resistance to comply with the EU court’s decision means the the “right to be forgotten” may soon become a more universal right.

Do you really have the right to be forgotten? Or is this censorship, plain and simple? Let us know in the comments.

Image via Google